First Annotations on Painting

by Manoel Veiga

(translated from Portuguese by Beatriz Viégas-Faria)

Published in the catalogue of the solo exhibition at the Virgílio Art Gallery, São Paulo SP, 2005; and in the folder of the solo exhibition at the Dumaresq Art Gallery, Recife PE, 2005.

Process

This last series of paintings and drawings I have been working on – applying acrylic paint on canvas or paper – represents the development of a work initiated at the end of 2001.

The paintings are executed on the floor; the canvas is stretched tightly over plywood, and it does not move until the work is finished. This process starts with preparing a very delicate mixture of various colors, some of which comprise light pigments, made up of very small grains (low density), while others comprise heavier pigments, made up of larger grains (high density). This very fluid mixture (the only paint I will be using) at first composes only one complex color.

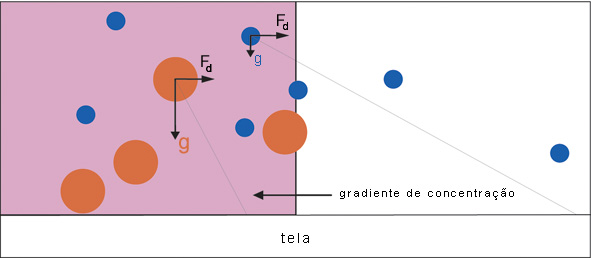

The next step is my attacking the canvas with a brush – and yet the brush barely touches it (this is done with the firm movements that will give the work its structural intensity). This much done, I carefully follow the drying up of the paint, interfering at certain moments, on specific areas of the canvas, by spraying water from a distance, very gently, aiming at creating different concentration gradients, which in turn will bring about the displacement of the pigments. These will naturally tend to occupy, by diffusion, the space where there is water only (just sprayed), therefore decreasing the difference in concentration and reducing the total energy of the system, which means there is a positive variation in entropy. In the displacing movement, the lighter pigments are more easily dragged by the diffusion force, and separate from the heavier pigments, that are subjected to a more intense gravitational attraction, proportional to their mass. As a consequence, the high-density pigments will be visible in some points on those places where the brush touched the canvas, for they “sink” more quickly, whereas the lighter pigments can be seen perfectly isolated at the outer edges of the mixture displacement.

Physics

Diffusion is the process by which molecules flow from higher to lower concentrations. The energy that provides diffusion with its force comes from the system’s thermal energy. At absolute zero (-273o C), the system’s energy is zero, and the movement of all particles comes to a halt. However, at higher temperatures, the amount of heat in the solution causes the Brownian movement of all particles in the solution (solvent and solute; in our particular case, water and paint). The Brownian movement is constant, and yet random. As the solution temperature increases, so does its thermal energy, and the particles move more vigorously. Adjacent particles collide, causing displacement; thermal energy becomes movement. The initial condition of our process, the very beginning of the painting, coincides with the brush-made marks that spread that previously prepared mixture of water and paint along some pathways on the canvas. At this moment, the Brownian movement is active, and so is gravitational force, pulling the pigments down, towards the horizontally laid canvas. When I add more water (solvent) to an area adjacent to the initial marks, a concentration gradient forms in that area which results in a movement of the particles towards the lesser concentration – in due time, this would annul the gradient itself. In my painting process, this is not the case, for I spray very little water (I am dealing here with an extremely thin layer of paint and water), and the quantity of water is reduced along the process due to evaporation, a parameter I can control by using an atomizer – it allows me to add more water to the area I am working on, at the desired moments. The pictorial outcome is, therefore, a recording of this movement of the color particles as caused by the force of diffusion in combination with gravitational attraction on the pigments, plus the absorption triggered by the canvas itself.

Area touched by the brush Water added with an atomizer

Fd = diffusion force / g = gravitational attraction

It should be pointed out that, once the painting starts taking form in this way, this new system will naturally behave according to the second law of Thermodynamics – intimately connected with the variation in entropy. In accordance with the second law, if possible, energy tends to spread, disperse, rather than concentrating in one single point. It should be noted that the concept of entropy does not entail the idea of disorder (a very common mistake). Scientifically, entropy variation is a way of measuring in qualitative terms how much change takes place in a system when energy is spreading in accordance with the second law. Entropy involves energy and its spreading around, and nothing else, and it does not relate to an appearance or final pattern. Entropy is not disorder, nor the measurement of chaos, not even a force of action. The diffusion of energy or dispersion towards other microstates is, in chemistry, the force of action. Entropy is the measure or index of this dispersion. In Thermodynamics, when an ideal liquid can be mixed into a larger volume, the increase in entropy is due to a greater dispersion of its initial thermal energy, which, however, remains the same.

Thanks to this unique mechanism, a coherent flow is introduced in the painting, tonal gradations form, and colors keep on separating in this very slow and delicate process. Part of the inaugural gesture remains there to be seen, and part of it is lost, obliterated and modified by another movement, the result of natural processes as induced by me: diffusion, gravitational attraction, capillarity. This is work executed in association with nature, making use of its movements.

Time and space

The flow that is introduced on the canvas, basically governed by the phenomenon of diffusion, changes that surface into a live system. This is a process that develops during a period of time, in the space of the canvas surface. Contrary to what may look like at first view, the displacement of particles is quite slow, and the process can take more than 10 hours to be completed, when then it is entirely recorded as a painting. Our brain, by means of inference, deduces this pathway and this is why we can reach an understanding of the whole movement in a glance, as well as its final moment, and even any of its intermediate stages. This gives us the chance to mentally retrace that entire route, by means of an intellectual operation, in a split second – either going back and forth along that movement, or stopping at any one intermediate stage, thus changing an already finished record into information which is alive again, dynamic once more, and then with an elastic time-span (according to each viewer).

Depreciated authorship

In the Western world, painting has long been linked to the notion of authorship, and that of a strong authorship, connected with a sort of demonstration of human willpower and its ability to construct with independence, to control nature. In face of the “problem” put forward by the human mind, a visual solution is generated by the hand of the artist (and more exactly by the gesture performed by the hand of the artist), now equated with authorship. Nothing should be left to chance, and chance has always been denied, or else much depreciated, even when this would make for a most implausible observation, as in the case of American artist Jackson Pollock and his use of gravity to make the paint hit the canvas. Always working with some unpredictability because he dealt with a force of nature combined with his own, Pollock himself vehemently denied this possibility.

In the way I paint today, I don’t deny the effects of chance; on the contrary, I acknowledge its presence and incorporate it into the process and, consequently, into the final outcome. While working, I induce the diffusion of pigments due to a difference in concentrations that I define; therefore, I am fully aware that I am creating a system where the second law of Thermodynamics clearly applies, unimpeded. We know the particles have a “tendency” to move in the direction opposite to that of the gradient; however, we cannot predict exactly how this displacement will occur. There is but a “probability” the event will occur, and this is what we deal with. As much as we know the physics involved, one thing is for sure: we shall never be able to control in a deterministic way the behavior of that many molecules as there are in the mixture of colors. We are not dealing here with the traditional manual process where the hand of the artist takes a tool (brush, spatula, etc) and applies a certain quantity of colored paste that can be shaped on a fixed surface. We are dealing here with an entirely different type of process, whose nature is physicochemical and dynamic, where the hand of the artist provides no more than the initial conditions – as relevant as they are, they are nevertheless no more than this: initial. Given that our system has few main variables (canvas, water, pigments), it was through the careful observation of each painting’s development and by having the knowledge of the theoretical points that describe and explain the physics involved that I was able to develop, in these last few years, a set of techniques and procedures that have allowed me to acquire a somewhat better control over the process and, consequently, of the final outcome. I act along with nature, by inducing, provoking, or restraining some of the phenomena characteristic of the process according to my desire and according to my primary purpose, that of making a painting.

In view of the above-exposed ideas, I can say of my authorship that it has been “depreciated” in relation to this series of paintings, since I openly declare my control of the final outcome to be partial and variable. It should be pinpointed that I am discussing authorship in its most traditional sense. I do not deny my authorial presence, for it is sufficiently clear, but I do seek results that will go beyond that, by being indicative of a relation of greater integration with that which surrounds us. I aim at reaching a closer proximity with nature by trying to present it “as” the painting itself rather than representing it “in” the painting. My present paintings reveal natural phenomena, and not their representations. Rather than being metaphors, they are direct indices of such phenomena.

Gesture

When reduced to the scale of a small photograph, these paintings undergo an alteration of its basic structure; one could say, of its essence. Under these conditions, the inaugural movements of the painting are evident – the gestures executed with a simple brush soaked in that single mixture. Most of what is generated after that by the natural phenomena will simply disappear or else become imperceptible to the naked eye. All of those complex movements in various scales, from the displacement of the relatively thicker fluid to the escapes of the thinnest particles, are deceptively reduced to the classic brushwork of an expressionistic quality. What is at stake here is not the denial of a certain type of gesture; it is instead a matter of getting right both the weight and the presence of all the elements that comprise these pieces of work. The mass of paint undergoes a whole sequence of internal movements, and this sequence depends on the very first minutes of each work, when I execute the marks with the aid of a brush. The flowing of the paint has an obvious causal relation with that initial condition, even though the relation may not be clearly visualized in the final outcome. It must be said that the gestures are simple, in so far as they are body movements, such as those introduced by Henry Matisse in mid-20th century – they are not born out of complicated or subtle wrist movements. In fact, those first moments determine whether a final balance is achieved between filled and non-filled space, space taken or else left empty, in an active relation between them – something I try to catalyze also through other indirect procedures that will tend to make the brain create subtle links between the white of the canvas and the areas filled with pigment. These are events that play a role as indices of something that must have taken place in some of those borderline areas – some sort of energy exchange.

Beauty

I am very much interested in that kind of beauty as found in nature, with its own canonic standards, frequently different from those of art. It is my understanding, though, that I attempt at touching both. From a conventional (one could even say classical), structural starting point, I make use of the touch of the brush and the movement of my whole body, thus preserving a link to our artistic traditions. In what follows, by our making use of an atomizer, as well as by otheur capitalizing on the dynamic action of diffusion and on gravitational attraction, and at the same time by our knowing probabilistic features of the established flow, a new and entirely different visual result can be created that reflects conditions found in nature. From the mutual influence these two worlds have on each other, a final structure is established, and having a broader apprehension/ comprehension of this structure depends on knowledge of that relation between nature and art.